Have you head of the Eudaimonia machine?

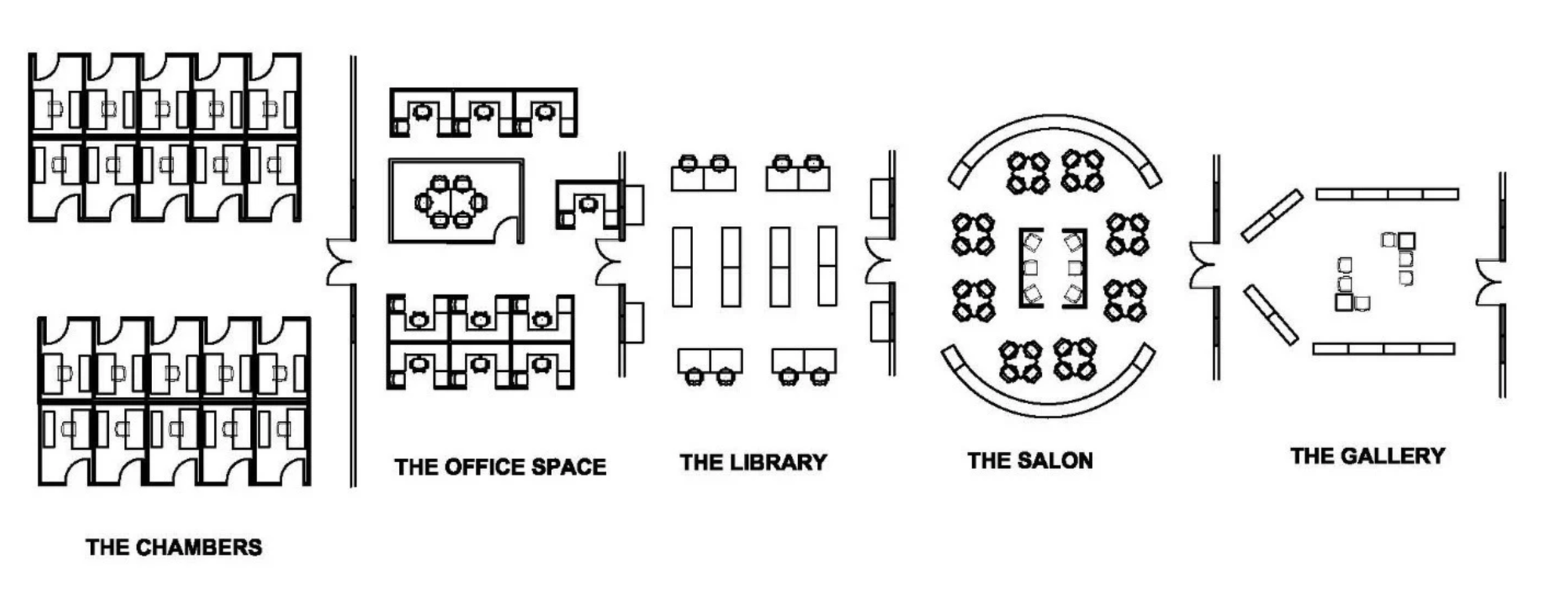

Imagine a one-story, narrow structure, a straightforward rectangle divided into five rooms, in succession. There's no quick escape route here. This design insists that as you move through, you're plunging deeper into the world of intense productivity.

You start in the gallery, the first room as you enter from the street. Inside, you'll find examples of remarkable work created within the building. It's a place meant to ignite your inspiration, setting the stage for a culture of constructive stress and peer pressure. It's a room that raises the bar, motivating you to bring your absolute best.

From the gallery, you step into the salon, the intellectual battleground. Here, the atmosphere oscillates between intense curiosity and lively debates. You can grab a cup of top-notch coffee, or perhaps even something a bit stronger from a well-stocked bar. Comfortable couches and unrestricted Wi-Fi create an environment where you can reflect, argue, and fine-tune your ideas, gearing up for the deeper work ahead.

Next in line is the library, a treasure trove of knowledge and the keeper of all the work produced within the machine. It's the epicenter of information, housing records, books, and resources from previous projects. This room is the machine's intellectual core, storing everything you need to supercharge your projects.

And then there's the office space. It's decked out with a standard conference room, a whiteboard, and cubicles with desks. This is the realm of low-intensity work, where you tackle the lighter aspects of your project. An administrator is on hand to help you fine-tune your work habits for peak efficiency.

Finally, you reach the heart of the Eudaimonia Machine - the deep work dungeons. These chambers are built for one purpose and one purpose only: complete concentration and uninterrupted workflow.

Imagine a six by ten-foot sanctuary, encased in thick, soundproof walls. Here, you can work for ninety minutes, take a ninety-minute break, and then repeat the process two or three times. After that, your brain has maxed out its daily capacity for deep focus.

The only twist in this story? Atleast for now, the Deep Work Dungeons exists solely in architectural drawings and plans.

It's an enticing piece of speculative fiction which leads us to this question — How might we craft our own Eudaimonia Machine, our personal deep work dungeon?

Let me take you through a couple of my own experiments dwelving deep into this topic. Dewane, the architect behind this concept mentions — "This remains, in my mind, the most interesting piece of architecture I've ever produced".

As fulfilling as it can be, the ability to do deep work has become extremely difficult. We're all "mental wrecks" in a way owing to On Demand Distraction platforms.

I sometimes feel as if I just have a goldfish-level three-second attention span. Sometimes as a "mental wreck", I've realised slowly, and steadily that keeping the focus razor sharp on one-single thing is a muscle that needs to be trained and developed. Now think of the larger-scale implication of a society which is not paying attention to anything, and is under constant threat—Ads (consumerism), News (emotional response), Short-form content (clickbait eye-candies).

"The ability to perform deep work is becoming an increasingly rate at exactly the same time it is becoming increasingly valuable in our economy. As a consequence, the few who cultivate this skill, and then make it the core of their working life, will thrive."

It's hard to shake this addiction when we want to concentrate. Every potential boredom in life—say, having to wait five minutes in a queue, sitting alone in a restaurant until a friend arrives—is relieved with a quick glance at the smartphone. One, two, 375 glances a day at the smartphone.

This is also one of the reasons why I've dumped to resorting to 'hacks' and 'mental frameworks' to be productive. Deep work doesn't happen without tweaking the root kernel of our mind.

If we study the lives of various influential figures from both distant and recent history, one will find a deep commitment to deep work as a common theme. Carl Jung's bimodal approach towards hiqh-quality work involved defined stretches to deep pursuits, leaving the rest open to everything else. As Naval Ravikant puts it — Rest, sprint and reassess.

High-quality work produced = (Time Spent) x (Intensity of Focus).

If we look at this equation more closely, it's an optimisation of two variables. The challenge with putting up high-quality work is not just about time-management. As shown in the earlier examples, the knowledge worker acted monastically — seeking intense and uninterrupted concentration.

The sixteenth century essayist Michel de Montaigne, for example, built a private library in the southern tower guarding the stone walls of his French chateau. Mark Twain wrote much of The Adventure of Tom Sawyer in a shed on the property of the Quarry Farm in New york. Twain's study was so isolated from the main house that his family took to blowing a horn to attract his attention for meals.

High-quality outputs of knowledge workers are extremely skewed based on their ability to focus. The gaussian distribution of productivity tiers looks like this —

- ~10% focussed on the job at hand (meaningful risk of getting fired)

- 10-50% focus: Meets expectatons, gets regular raises

- 50%+ focus: Superstar, 10x engineer, destined for greatness.

All said and done, focus is still a finite resource. Just like memory, attention and time. We use finite amount of focus each day, and that gets depleted as we tend to use it.

James Clear popularised the 4 Burner Theory wherein —

Picture a gas stove with four hobs. One is for family, one for friends, one for work and one for your hobbies. Now, they all burn away nicely on medium heat.

But when you want to turn one of them up, you need to turn the other ones down.

So you could turn ‘work’ to full heat, but you either bring all three down a notch or even turn one totally off. (The 23-year-old investment banker sleeping under the desk in Goldman Sachs’ New York office springs to mind…).

As a concept, the idea is sound — optimising for the 'work' hob might put backstage to the 'family' hob, or the 'hobbies' hob. But it doesn't always have to be that way.

The canister next to the stove which provides the available energy. Unlike the metal canister, we can increase the energy available to us by — (a) physical fitness and adequate nutrition, (b) meditation and learning new skills, (c) time in nature and meaningful relationships helping us become more emotionally aware.

Everything has an inherent growth loop. Continuing along the 4 burner analogy, we can balance all those hobs (work, hobbies, family, relationships) as long as the cannister is strong, big and wide.

Member discussion