Think about the past year, 2021 for a second.

2021 felt like five years packed into one.

— Joe Biden becomes the President of United States.

— SpaceX launches an All-Civilian Flight.

— Tokyo Olympics happens.

— Kabul falls to Taliban.

— Historic breakthroughs (Alphafold/Quantum Supremacy etc)

— Pandemic is not done yet (far from it)

— Rise of NFTs, DAOs etc

Against this backdrop, I was tempted to write a letter as a future parent.

What would the educational landscape of my unborn child look like?

Having been passionate about creating tools and environments in the educational space, this prompt helped me envision the ecosystem much more vividly and to think through various steps that we might have to take now/later.

What would the dream school be designed as? (amidst all these uncertainties)

Stretching it a bit further, how would it be different 10, 20 or even 30 years down the line? Would it even be a ‘school’ in the conventional sense?

Technological Singularity is near

All this stemmed from a stark realisation that we are living in an infinitely complex and rapidly accelerating world right now.

Ray Kurzweil aptly describes this phenomenon as the Red Queen Effect. As the tech singularity is approaching, the floor at which Alice is running is actually outrunning Alice herself.

The pace of advancement when it comes to hardware, software and even the ever-growing intermingling of social systems are causing our professional roles to become more and more diffused.

How, then, would our educational system evolve to accommodate such blitzscaling?

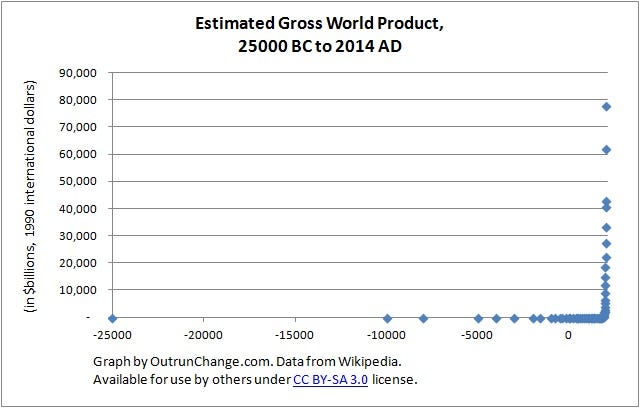

If we just chart out the Gross World Product from 10,000 BCE to 2019, it almost looks like this…

20 years from now, the rate of change will be 4x what it is now.

In 10 years, the paradigm shift would be 2x and in 100 years, the paradigm shift would be 1000x!

The child who is 10 right now, would experience a year of change in 11 days, when they’re 60.

Our society is moving towards an acceleration shock.

The world is an incredibly complex place and everything is changing all the time. We can plan our careers but have no idea what’s going to happen in the future.

We have no idea what industries we will enter, where we live, or even how we are going to contribute to the world.

The best education which our children can get is to be more prepared with such uncertainties (to accomodate such 2x, 20x or even 100x paradigm shifts)

In essence, they need to learn to be more malleable.

If we indeed do put in the futures-thinking hat, what could then be the principles we anchor our children towards as we dive into the future?

Let us look more closely.

We need more swiss army knives

The education which we provide has to accommodate for the fact that we can find any information online at the click of a button.

So, instead of optimising for merely information retrieval, we should let our children optimize for information connections.

They should build better thinking systems for linking our thinking.

After all, why shouldn’t we?

It doesn’t make sense if they are forced to take history lessons. Or other subjects that they don’t like.

Internet is the greatest weapon of knowledge ever created.

The skills we might currently need is in learning how to learn, on the fly; using the marvels of the internet.

Conventionally, the problems we used to solve where much more structured and known-in-advance (for eg, placing packages on a conveyor belt).

However, If we look at our current work as knowledge workers, it’s mostly just various kinds of problem solving. In one way or the other. In one form or the other.

We see new problems everyday which we are not yet trained to solve. There is a little bit of everything.

The problems we face nowadays have moved from the realm of known knowns to the unknown unknowns.

Here, *learning new topics* becomes more important than *having learnt essential topics*. As we can’t determine, nor predict what those topics could be.

All we need is a smartphone and maybe, an internet connection to access MIT and Yale lectures online, complete course work, read brilliant blogs and various great books, all for free.

And, eventually, the children get better trained to —

Build. Write. Sell. Code. Edit. Speak. Create. Draw.

They become better swiss army knives. Sometimes, the specialist perspective might become lopsided while dealing with such issues. As the saying goes, “If all we have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”. The generalist, however, thrives in such complexity, knowing a little bit of everything.

In the first phase, children go breadth-first to find their niche. Once they do that, they narrow down and gain expertise by focussing on the depth of knowledge later on.

In this evolution, it would be interesting to see how we design keeping their core motivations in mind. After all, everything and everything could be learnt. Only motivation seems to be the most scarcest resource. At least for now.

Thinking and Learning go hand in hand

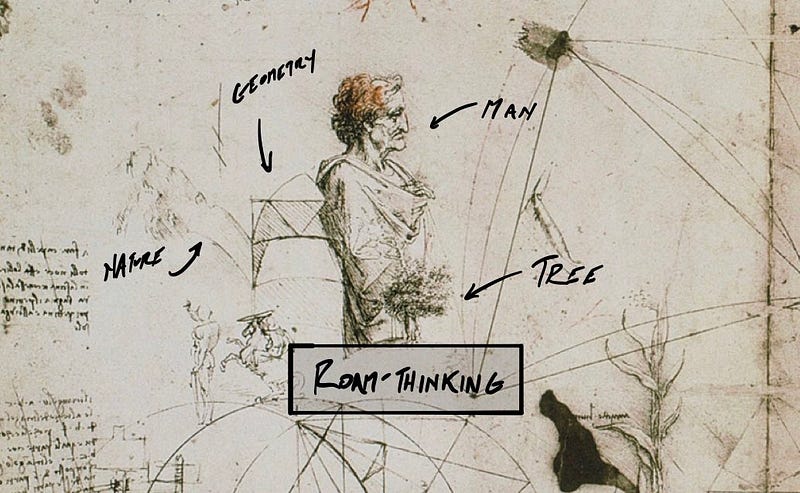

Improving the craft of learning goes hand-in-hand with improving the craft of thinking.

By thinking about thinking, we learn how to learn.

How we carefully articulate our thought processes also helps us to structure the information we assimilate.

The process of synthesising complex topics, forging those associations and coming to a point that you could share a TED talk on that topic might eventually require constant rumination and clarifying ideas in our head.

The mental gymnastics is as follows: We process information in the form of hazy gases, condense these gases in the form of malleable liquids, and eventually freeze these liquids to form condensed solids, which eventually become the foundational building blocks of our knowledge.

We need to train our children to become masters of this process of alchemy. To crystallise ideas in a clearer form, and optimising them for sense-making.

We want to develop children who are *better* than we are so that they can solve the problems we can’t. As Einstein once said, ‘We cannot solve problems with the same level of thinking we used to create them’. They need to transcend the conformity of our instructions.

We need to do this as the only certainty in this world is that there is no certainty.

Stronger dose of Cohorts, Coaches and Curiosity

The modern day school should provide adequate tools and resources for satisfying children’s curiosity rabbit holes.

They could, of course, do it online. On their own free will as well, without needing any facilitators or schools to do so.

However, the modern schools provide them structured learning pathways in the form of expeditions, with facilitators/coaches mentoring them along the process.

The biggest advantage which schools could provide in this landscape is through a trusted curation. After all, there is a constant information overload, and that we are trying to sip water from a gushing hosepipe. Content curator becomes more crucial when compared to the content creator here.

These curiosity rabbit holes thrive in the presence of coaches and cohorts.

Curious to learn how to deploy a smart contract?

Come join this expedition with a group of 20 other students who come together to launch a decentralised app.

Curious to learn how electric cars work?

Join an expedition to use first-principles methods, understand the business model of Tesla as to why electric cars are attractive and even pitch it to ‘fictional’ stakeholders representing Tesla.

These guided learning experiences/expeditions could help children to shift the learning experience from being a mere passive regurgitation of information to a more engaged, involved, project-based approach.

Teachers then become facilitators who guide children through various such journeys. The modern coach/teacher/facilitator guides the student towards the rabbit holes, but doesn’t exactly tell them what to do.

They just orchestrate the magic and excite them enough to keep them motivated in such expeditions. I’d prototyped a model for such an expedition here to visualise better. Eventually, the school becomes an hub for accessing curated high-signal specific knowledge in the shared presence of a community.

We are already seeing this happen through modern schools such as Galileo, Sora, Synthesis School etc allowing for a more active learning experience digitally.

This might very well be the norm sometime soon.

Of Teachers becoming Coaches and Facilitators.

Of Students becoming Collaborators.

Of Cohorts becoming Universities.

Ultimately, by providing a stronger doze of Cohorts, Coaches and Curiosity, schools will allow children to thrive and prosper in this complex and dynamic environment.

Passing the baton from one generation to another

Even though we had earlier pointed out how fast technology and society is evolving rapidly, it’s to be noted that not all technology advances in the shape of an upward facing hockey stick graph.

Sometimes, it does go backwards in case we don’t put significant effort into them.

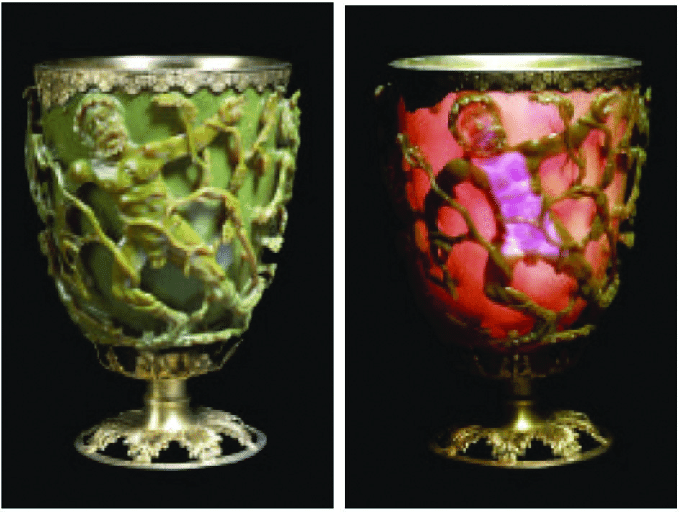

Take the Lycurgus Cup as an example. It was made in 4th century by Romans using dichroic glass, which shows a different colour depending on whether or not light is passing through it: red when lit from behind and green when lit from in front.

Dichroic effect is achieved by the addition of tiny nanoparticles of gold and silver in colloidal form throughout the glass material.

How did the Romans even know about such advanced material science, and that too in 300 AD?

When the Roman empire fell, the knowledge on how to make this was also lost.

Another example is that of the Antikythera mechanism.

A mechanical calendar which was used to even accurately point out the alignment of planets, or even the timeline of the next Olympic games. This was made out of 37 different bronze gears working in clockwork to accurately track the astronomical positions and eclipses even decades in advance.

It’s mind-blowing to think that in 200 BC, you had something with 37 meshing gears and 223 teeth explaining the position of the sky, stars and even the Olympics.

The knowledge was lost over time, and mankind had to learn the concepts of developing such complex mechanical arrangements from ground zero.

In both these examples, there was a loss in intergenerational transmission and mankind had to start from scratch again.

It’s not just about the knowledge from those archaic times.

Let’s take Apollo 17, the last manned mission that ever happened. And this was back in 1972.

Isn’t it surprising to think that it’s currently 2022 and we have not set our footprints on the moon yet?

Unless we put in the effort, technology dies with us. It is an illusion to think that technology would always constantly evolve.

Intergenerational transmission of knowledge cannot be solved just by taking some field notes.

To demonstrate the limitations of such knowledge transfer, the great philosopher and teacher Michael Polanyi wrote a very detailed explanation of the physics of riding a bicycle — ‘That adjusting the curvature of your bicycle’s path in proportion to the ratio of your unbalance over the square of your speed’.

Knowing the physics and the formulas behind riding a cycle doesn’t actually guarantee that you know exactly how to ride a bicycle. It’s like lecturing birds how to fly. It’s not about the lecture, it’s about the practise. in fact, you will probably be worse off trying to calculate these things while figuring out how to apply this while riding.

The knowledge required to ride a bicycle can’t be fully captured in words and conveyed to others.

There is a lot of tacit understanding required to replicate something like a Lycurgus Cup or a Antikythera mechanism. This cannot be merely written down in words. And this becomes crucial to do a proper hand-off in the form of apprenticeships where students can learn the actions and key principles in-situ, while the master is performing the craft.

And this case is not just about all these, it’s even comes down to grandmother’s wisdom. How do our children retain the wisdom as they move further and further away from their grandmothers.(tha includes knowledge ranging from preparation of traditional cupcake recipes to ancient herbal practises).

Our children should stand on the shoulders of giants. We aren’t supposed to reinvent the wheel all the time.

Proof-of-work is the only way

As we move away from proof-of-credentials, we are moving closer to proof-of-work where we vet for our skills through our portfolio of projects that we have built or launched.

We need to teach our children to document their skills and thinking better. After all, ideas are only as good as our ability to communicate them.

This would help them showcase and stand out in a better way.

I question, therefore, I am

There’s a common saying in educational circles: Don’t teach students what to think; teach them how to think.

The idea goes back at least as far as Socrates.

Today, we call the Socratic method as a way of teaching that fosters critical thinking, and to question our own unexamined beliefs. Such questions might lead to discomfort, or even anger on the way to understanding, but these are the best ways to learn.

By asking great questions, we probe deeper into the meaning of our existence. Great solutions start with framing great questions.

Here’s an example of a famous example featuring a welding robot where we can see how this kind of persistent enquiry can help us come closer and closer to identifying root cause.

- Why did the robot stop?

— The circuit is overloaded causing the fuse to blow. - Why is the circuit overloaded?

— There was insufficient lubricant in the bearings. - Why was there an insufficient lubricant in the bearings?

— The oil pump on the robot is not circulating sufficient oil. - Why is the pump not circulating sufficient oil?

— The pump intake is clogged with metal shavings. - Why is the intake clogged with metal shavings? …

And this goes on until we get to the root of the cause.

Not just in this example of troubleshooting issues with a welding robot, the ancient Greeks had given rise to the birth of modern philosophy by constantly probing life’s biggest questions.

What is the purpose of our existence? Is there any meaning at all?

It can even be that the questions might not probably have immediate answers, but the spirit of enquiry shapes their thinking, and eventually shaping their reality in this process.

Tinkering in the truest spirit

Every year, the Marshmallow challenge takes place between a bunch of kindergartners and MBA students.

The participants are given 20 sticks of spaghetti and asked to make a free standing tower with marshmallows. In the end, the biggest Eiffel tower of marshmallows wins the game.

What’s surprising about this experiment, is that almost all the time, the kindergartners win. And this result was not an outlier. The experiment was repeated hundreds of times with the same exact result.

The MBAs actually perform the worst on average when it came to building marshmallow towers. There could have been multiple factors which led to this. MBAs tended to plan their way to an optimal outcome and then execute the plan.

Furthermore, adding incentives, like prizes or cash only makes the problem worse — planning goes up and average tower height goes down. In contrast, kindergartners do something much different.

Instead of wasting time trying to establish who is in charge, or in trying to make a plan-of-action (or even worse, a three-step framework), they simply experiment over and over until they find a model that works.

As adults, we are constantly taught to plan out a course of action, to optimise for the outcomes to be successful. This works great if we know the exact outcomes, but it fails terribly when the problem or the solution are unknown. It’s surprising how much the mindset of ‘If we are failing to plan, we are planning to fail’ has been ingrained in us.

It sometimes us stifles us, obscuring our vision to look at the world with child-like wonder.

This mindset of just experimenting and trying out various things without being worried about being wrong has led to the kindergartners getting better results all the time.

Children should continue to adopt tinkering over planned methodological experimentation. Which means more play and less studying. They should learn to play, and play to learn.

In essence, that’s what scientists do all the time. They are, in fact, children who haven’t actually ‘grown up’.

Children rigorously using logic and experimentation to understand the physical world, converge, and gradually discover the truth. They continue to tinker around and have fun in this process.

This coming century would probably need more of these. To allow children to tinker with an open mind, and not constrain them with rigid methodologies.

Children just need to embrace this spirit of tinkering. We need to just tell them to just *be*.

I’m struck by a quote by Picasso which describes this. “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

And this means opening up various dimensions of problem solving, and to declutter them from various status management cues which otherwise hamper creative problem solving for adults.

In Conclusion

For a child who is 10 right now, would experience a year of change in 11 days, when they’re 60 years of age. As we proceed, the educational systems that support the growth of our children should also be accommodate the rapid acceleration of our societies.

In sum —

- Children should be trained with the generalist mindset and be equipped to build, write, sell, code, edit, speak, create and draw and become Swiss-army knives in this process

- Improving learning outcomes starts with improving the thinking outcomes. We need to train them to become masters of synthesis and become better idea connectors.

- The three Cs of modern schooling involve — Curiosity, Coaches and Cohorts.

- Every soft and hard skill becomes productized. Every skill becomes easier to communicate online and hiring would essentially take place through proof-of-work.

- Systems for intergenerational knowledge transfer should be made possible through apprenticeships.

- Advocating the spirit of enquiry and embracing the unknown. “The only true wisdom is in knowing that you know nothing‘’— Socrates

- Embracing the child-like wonder and curiosity to tinker, experiment, make mistakes and gradually discover the truth in this process.

Footnotes

- While displaying the case for tinkering as a pedagogy, and critiquing the traditional systems of education, I should have also considered the second order effects of our traditional systems, and not just the immediate consequences. From this Farnam Street article, we should consider to practise thinking about not just the consequences of our decisions, but also the consequences of our consequences. There could have been potential benefits of traditional schooling which I might have not taken into consideration.

- The title, ‘Pedagogy of the uncharted’ is inspired by Paulo Freire’s brilliant masterpiece, Pedagogy of the Oppressed which has shaped some aspects of my thinking with regards to education as a form of liberation. Shoutout to Aniket for the suggestion and early review of the first draft.