Sometimes, forgetting is good for your memory. If you are forgetting the concepts at a 'spaced interval' in a conscious way, you might actually make your memory more concrete.

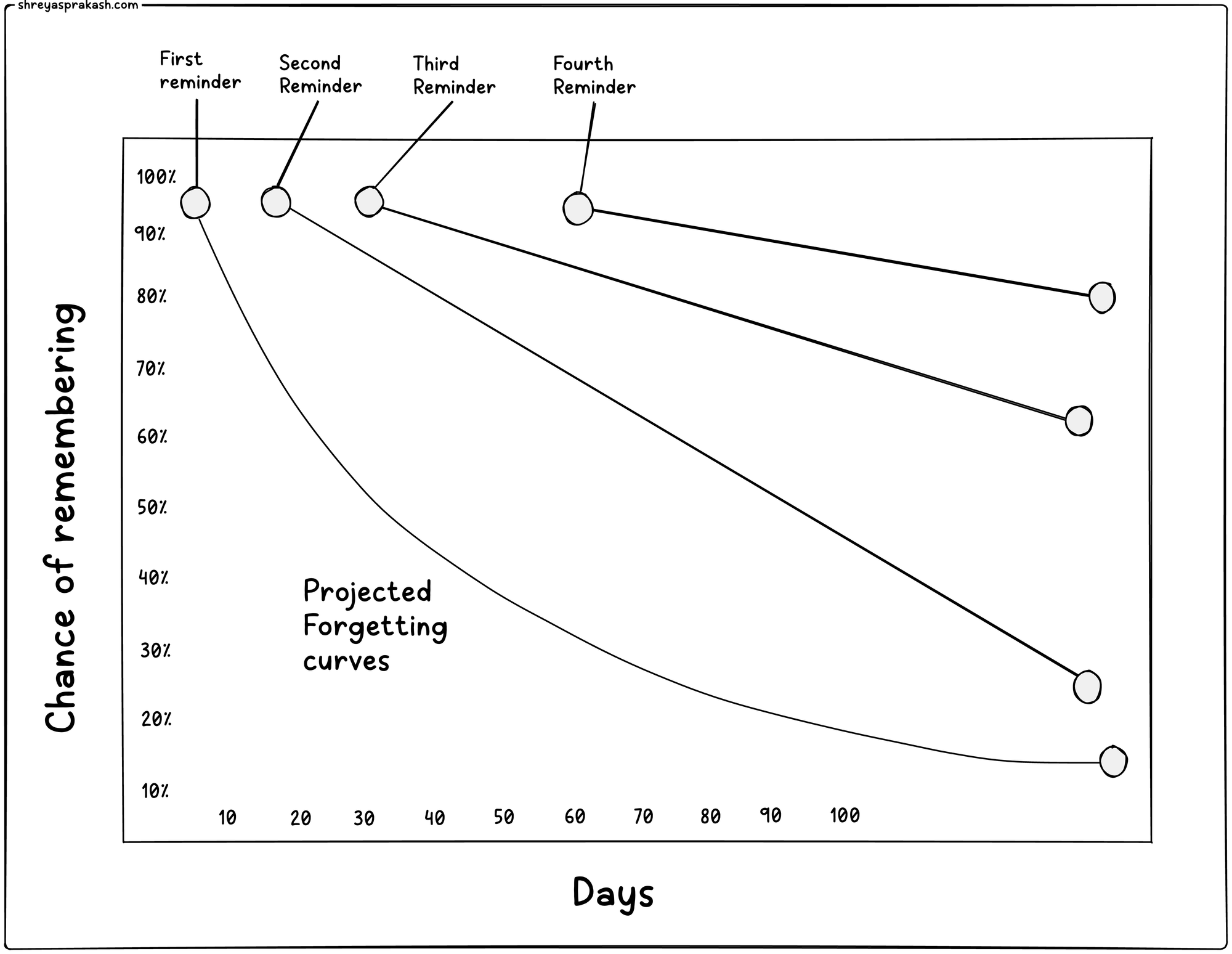

This could be best illustrated by the repetition curve graph below:

Our memory is prone to logarithmic decays as time passes by. But as we keep recalling the ideas/concepts at certain intervals, you can see here from the graph that the slope of decay for such logarithmic curves tend to flatten a bit.

More recently, spaced repetition using flashcards have been popularised by internet writers such as Andy Matuschak, Derek Sivers and researchers such as Stian Haklev. In a nutshell, spaced repetition's value lies in dynamically scheduling questions to be reviewed at a given time interval.

Say if you learn a new word in a foreign language, you’d want to practice it again a few minutes after hearing it, then a few hours, then the next day, then in 2 days, then 5 days, then 10 days, 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 8 months, etc. After a while it’s basically permanently memorized with a rare reminder.

Spaced Repetition Software does this for you, so you can just give it a bunch of facts you want to remember, then have it quiz you once a day, and it manages the intervals based on your feedback. After each quiz question, if you say that one was easy, it won’t be introduced for a long time, but if you were stumped, then it’ll ask it again in a few minutes, until you’ve got it.

This could be a simple set of flashcards, and we have some good softwares that support flashcards for spaced repetition such as Anki (It also comes as an Android/iPhone app with all the customisations which an SRS-nerd might need)

And in this way, you're giving it the power to program your attention. (It's like a 'cron' for your mind)

I've been previously in the camp which despised the need for 'rote learning' and memorisation, but I've now turned rogue and have started believing more on the need of having a well-oiled memory management system (even more during these times of LLMs).

The more often you offload your memory to the computer, I think we take a hit, and slowly start losing our competence as well. Imagine you just didn't use the calculator, and relied on computer for even the simplest of calculations, what harm would it cause? Certainly, all these are googleable, and you could still get the 'job done'. But there is merit in having some of them in your immediate accessible memory (RAM).

This was as a result of reading this excerpt from Richard Hamming's The Art of Doing Science and Engineering where he mentioned about his experience working with John Turkey:

I had worked with John Tukey for some years before I found he was essentially my age, so I went to our mutual boss and asked him, “How can anyone my age know as much as John Tukey does?” He leaned back, grinned, and said, “You would be surprised how much you would know if you had worked as hard as he has for as many years”. There was nothing for me to do but slink out of his office, which I did. I thought about the remark for some weeks and decided, while I could never work as hard as John did, I could do a lot better than I had been doing.

In a sense my boss was saying intellectual investment is like compound interest, the more you do the more you learn how to do, so the more you can do, etc. I do not know what compound interest rate to assign, but it must be well over 6%—one extra hour per day over a lifetime will much more than double the total output. The steady application of a bit more effort has a great total accumulation.

Compound interest is indeed the eight wonder of the universe, and if we do the math—

One extra hour per day of SRS memorisation can easily compound to helping us ingest roughly 6,000 atoms of knowledge each year.

And with this newfound ability, you could certainly invest in remembering trivial factoids. But I think, this could extend a lot more beyond just that. You could even engage more deeply with whatever matters most to you. If we take the analogy of a large language model, the quality of the training set matters. Personal memory systems are akin to that as you're directly feeding your human RAM.

Slow, compounding progress is a subtly powerful force. Regular weightlifters might not perceive their progress in every session, but as the weeks go by, they’ll find they can handle loads which would previously have flattened them.

In this essay, I would NOT go deep into the following questions: (a) What are the various types of SRS systems? (b) What software to use? (c) What is even SRS? How does it work? etc.

I would be focussing more on – How to reap the most value out of your SRS system? What to even memorise? And will condense and distill the key ideas around space repetition systems out there on the internet.

What to even memorise?

- Syntaxes – As someone who has been slowly learning programming on the side, I've been using the system to learn syntaxes of common languages that I use on a weekly basis. This includes SQL functions, React code examples, programming patterns etc. These are framed in the form of a 'question and answer flashcard'. (Refer to Sasha Laundy's essay on Using Flashcards to become a better programmer)

- Mnemonic systems – This is a meta technique to help you memorise certain numbers and keywords by converting them into images so that you could memorise them easier.

- Greek alphabets – Alpha, beta, gamma, delta, epsilon etc.

- The NATO alphabets – Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Golf, Hotel, India, Juliett etc. (did you know that Juliett was deliberately spelled with two Ts so that French personall wouldn't drop the T when pronouncing it..)

- Morse code to communicate privately in public (or in case you spot an Unidentified Aerial Object and would like to try communicating with them using light signals)

- There is even a deck on the Anki website called as the "ultimate geography" which has country locations, capitals and flags.

- Phone numbers of important people so you won't feel like a moron when your phone battery dies and you have to borrow someone else's.

- If you're on a diet, memorizing nutritional content, calorie counts of common meals, weights of food, common food substitutions etc.

- Birthdays. After the death of Facebook birthdays, it's been increasingly difficult to keep track of birthdays (despite having this on your calendar, it's highly likely that you forget them)

- List of latin phrases (modus operandi, cogito ergo sum, primo, secundo etc.)

- Trivial factoids such as your driver's license number, etc. If you have concerns of security for sensitive information, you could put a question such as "did you remember this well enough to know you know it? If not, go check".

- Interesting puzzles that you can pose to people and their solutions (math puzzles, word puzzles, lateral thinking puzzles etc) (I see myself running out of ideas to intellectually titillate my nephews)

- Andy Matuschak also talks about having some visualisation exercises to reinforce happy memories (SRS is cron for your mind, and your programming attention to things and events that matter). For eg: "visualise your wedding day", "when you first graduated and received distinction", and sometimes even certain painful memories if you'd like.

- Aesthetic kindling – Have an interesting image you found while browsing the web and have a provoking prompt such as "What do you find striking about this?", the back of the flashcard can just have nothing. Art could also be a great prompt for aesthetic kindling and getting a better sense of why/what feels certain way. "Stop thinking about artworks as objects, and start thinking about them as triggers for experiences" – Ray Ascott. These probes can also help us cultivate our emotional visualisation skills. And those are life skills that come in handy.

- Prompts to stay in touch; front – "visualise your friend Sam, is there anything you'd like to say to him?". Perhaps, this is your long distant friend who you've been out of touch with, and this provokes you to flash a memory, and get in touch with him again.

- Installing habits in your mind – Have you ever looked back at your day and found you've either omitted to do something, or did something dumb? This is a case of not knowing something: not knowing what should be done when; not knowing what should be avoided and put out of sight; not knowing the reasons why certain things are important. This is an area where memorization has unrecognized importance. If you can memorize the specific reasons why certain actions are important (exercise, diet, working hard, whatever), and if you can memorize them so well that they can be called to mind in a second, then you're much less likely to get off track or have a momentary lapse in judgment. It's like asking someone, 'have you done exercise or not?'. Even if they haven't done any exercise, this might compel them to do so, or create a habit

- SRS is helpful to install habits, as you could leverage it to think more deeply on why certain goals matter to you more than others. A systematic approach towards installing habits would be by first identifying important habits, actions we would like to cultivate, then creating specific, detailed reasons why these actions are important to you. Then creating vivid mental images or scenarios for each reason, engaging all senses and emotions in these visualisations. Then using spaced repetition techniques through Anki flashcards, to reinforce these memories.

- Some other techniques of installing habits, also involve specific questions to chunk habits in sequence – the front side card could be: "When I pick up my toothbrush in the morning"... and the back side of the card could be "get my phone and open Anki"...or..."do 10 pushups"

- Lightweight optional tasks – Such as cleaning your room, have you looked at who's linked to your blog recently? Or even work-related lightweight optional tasks such as your OneDrive file/folder cleanups, overview of your product's NPS scores etc

Some tips on using Anki flashcards

- It's advisable to just have one deck with all your cards. Everything in one place is better, and this way, it just makes it easier for your to cultivate the habit of going through a particular Anki deck everyday. If there are multiple decks, you might probably run out of time to have this as a habit of practise, and this ritual is very important for spaced repetition systems to work successfully. Just doing 10 minutes of everyday practise has much more ROI. Also, putting cards from different subjects together improves the learning process (much more varied and fun)

- Based on Matuschak's suggestion, I've customised the Anki system of repetition into three different categories of intervals: (a) max 1 day – a deck which contains thought patterns I want to review daily. (b) max 21 days – a deck which contains formulas and concepts I want to retrieve readily. (c) max infinity – a deck which contains all the cards that I want to learn but don't absolutely need to be able to recall immediately. In other words, I'm giving a priority queue to the cards, as not all cards are equally important for recall (for instance, an SQL query which is a work-related function might be more important than my driver's license card number)

- Some advice by other flashcard enthusiasts recommend to mess around with the deck options (Decks –> Gears icon –> Options). For example, if you feel the daily limit of 20 new cards is too high or too low, just change it. Personally, I prefer to get new cards shown in random order, than in order added (New Cards –> Order). Also, I suggest changing Lapses –> New interval to around 20%. This way, when you forget a card, it does not get reset completely, but instead reduces the interval to 20% of what it used to be.

- Also, don't be afraid to suspend the cards you don't need. Perhaps, you don't really want to exactly know what the capital of Aruba in Central America is, and you keep forgetting it. Just suspend and don't worry, it might not really be that important (for you)